Managing work/life balance teaching from home

I taught my first online course in the late 1990s. I had done my homework, reading up on everything I could find about teaching online, attending conference sessions about teaching online. While the Internet was out of its infancy, it was still in toddlerhood, so there wasn’t a ton of information out there about teaching online. For that matter, there wasn’t a ton of information about the Internet itself. Some time in the mid-1990s, my wife, who was a reference librarian at the time, had a file folder labeled “Internet.” That pretty much sums up how little information there was.

Anyway, I learned everything I could about teaching online, and then I did it. I taught fully online. The one thing that no one warned me about was the exhaustion. I felt like I was teaching all the time. Why was that?

For a face-to-face class—and by face-to-face I mean in a physical, three dimensional classroom—we mentally gear up to go in. We review what we’re going to cover, we put on our game face, don our teaching persona, step to the front of the classroom, and go. Teaching is a performance, and just like an actor or musician, you have to enter that space ready to go. And then we’re “on” for whatever length of time our class or classes are scheduled for. Growing up working class, I defined “work” as physical labor. When I started teaching, it took me a bit to figure out that teaching was also work. While it wasn’t physically taxing, it was mentally draining. Don’t worry. I have since amended my definition of “work.”

When we teach face-to-face, we know that we’re on from, say 9am to 12pm. Shortly before class, during class, shortly after class, students are asking us questions—questions about the material, questions about assignments, questions about course policies. And when we answer those questions, other students usually hear those answers, too. It’s a pretty efficient system. One student in a class of 50 asks about a course concept, and all 50 students—or at least the ones paying attention—hear the answer.

After that, we still have plenty of work to do—email, grading, reading, writing, committee work—but it’s qualitatively different work from the teaching performance. It doesn’t require the need to be “on.”

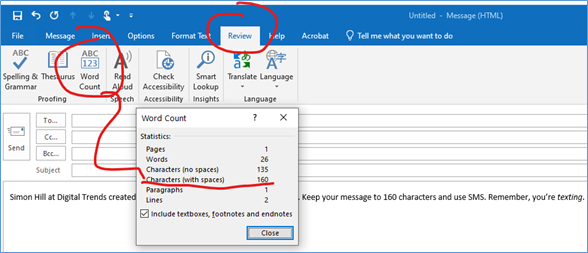

When teaching online, the primary way students get their questions answered is through email. What would have been a quick, after-class question takes three times as long – to read the email, to respond to the email with a clarifying question, to read the clarified email, to write the email, to edit the email (don’t let your exasperation show; yes, we know it’s in the syllabus), and then to read the student’s follow-up question, and repeat. And, of course, this is all interspersed with other tasks. And it takes time and energy to switch from one task to another (see this blog post for a demo).

Tips to help you feel like you’re not working all the time

-

Create a designated workspace. If you’re lucky, you have a home office. Use that space only for work. Do not work anywhere else in your home. When I’m in my home office, I’m working. When I’m in my living room, I’m not working. And for the love of God, do not work in bed. If you’re not lucky enough to have a home office, set aside one corner of your couch or one side of your table as your designated workspace. Relaxation happens on the other side of the couch. For meals, sit on a different side of your table. Designated physical spaces can help you separate “work” from “home.”

-

Set designated work hours. I work from about 8am to 3:30pm for two reasons. One, I’m a morning person; when my circadian rhythm dips mid-afternoon, my brain turns to sludge. And two, in the summer, my home office turns into a sauna about mid-afternoon. Whatever your work hours, don’t work before your workday starts, and don’t work after your workday ends. There’s nothing in your email that can’t wait. Designated hours can help you separate “work time” from “home time.”

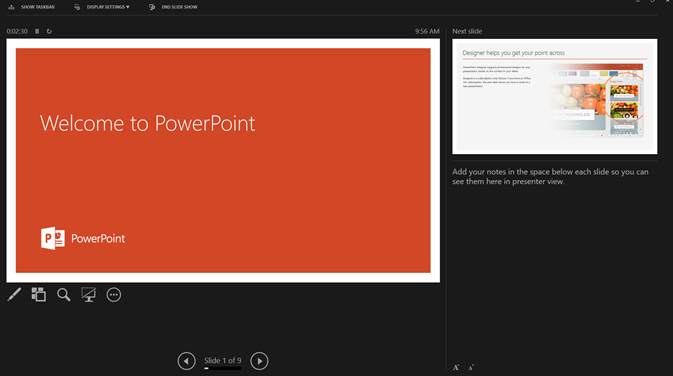

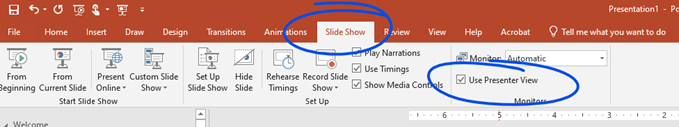

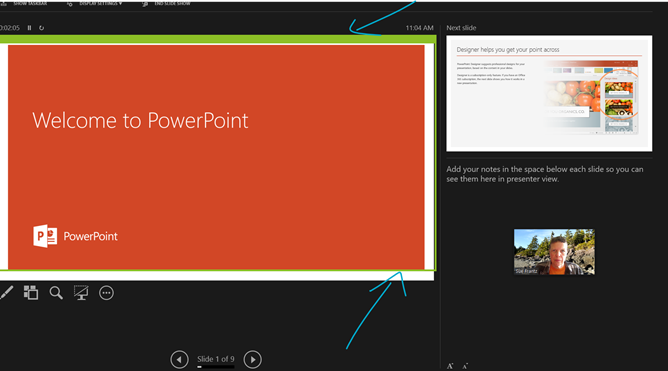

- Add transition time. I didn’t realize how much I needed transition time from teaching to being home until I started teaching via Zoom. The first day I did it, I ended class and walked out of my home office. And, BAM! I was home. It’s the closest I’ll probably ever come to feeling like a time traveler. Now when class ends, I stay in my home office for 15 to 30 minutes—tending to email, making notes about changes I want to make to what I just covered in class, reading an article or two. By doing that, I give my brain time to slide out work mode and into home mode.

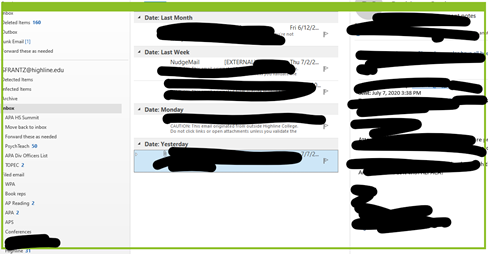

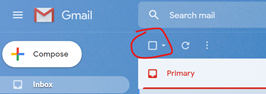

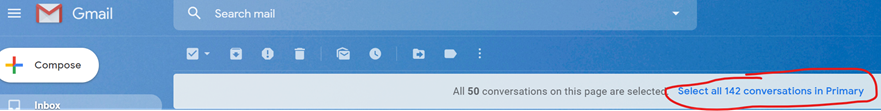

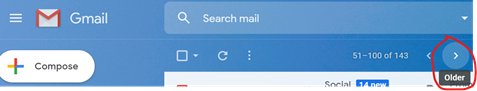

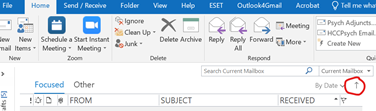

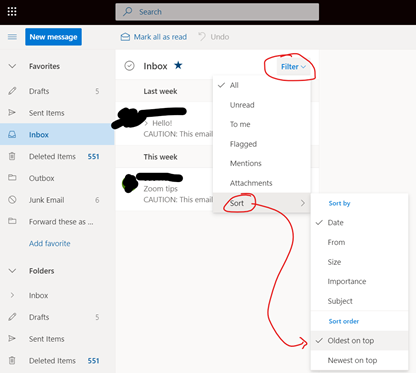

- Clean up your email. What’s in your email inbox should only be what you’re dealing with today. In this blog post, I walk your through how to get your email under control and how to keep it under control. Having pages and pages of messages in your inbox can make you feel like you’ll never get caught up. And, frankly, it’s easier for important messages to get lost. If you lose that message from a student or a colleague, they will write you back, but then you’ll have read their questions twice. There’s no reason to do double the work.

- Take your work email off your mobile devices. If you’re sitting in your living room watching Apollo 13, and you pick up your phone to find out how old Tom Hanks was when the movie was filmed, we both know that if there’s a work email notification, you’re going to click on it. And just like that, you’re working again.

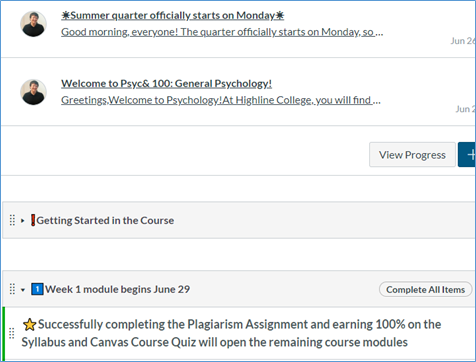

- Note common student questions and address them with the class. If a few of your students have asked the same question, it’s time for a course announcement. If it’s a question answered in your syllabus, consider adding a question to your beginning-of-term syllabus quiz. If you don’t have a beginning-of-term syllabus quiz, consider creating one. In my courses, students have to earn 100% on the quiz to open the rest of the modules in the course. Since my students can take it multiple times, I’ve discovered that some of my students—without reading the syllabus—take their best guesses at the questions. And then retake the quiz, making different guesses. Next term I’m adding a few points extra credit for getting all of the answers right on the first try.

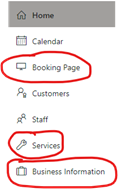

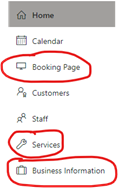

In the Bookings left navigation menu, there are three areas we’ll be using.

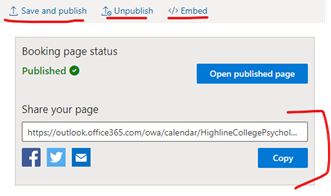

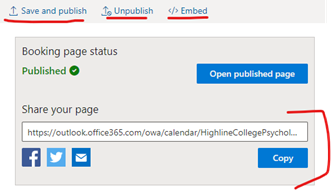

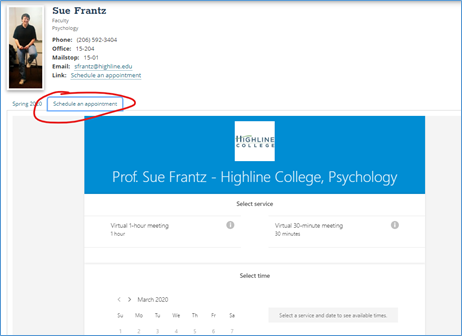

In the Bookings left navigation menu, there are three areas we’ll be using. Here you can find your Bookings page url. Give this your url to your students; post it in your course management system, for example, or add it to your email signature. Students—or anyone else—can use it to make an appointment with you.

Here you can find your Bookings page url. Give this your url to your students; post it in your course management system, for example, or add it to your email signature. Students—or anyone else—can use it to make an appointment with you.

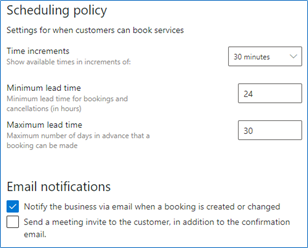

“Time increments” refers to the times students can choose from to start an appointment. Since mine is set to 30 minutes, students see times like 12pm, 12:30pm, 1pm, etc. If this were set to, say, 15 minutes, students would see 12:15pm, 12:30pm, 12:45pm, etc. This doesn’t affect how long the appointment may be. We’re not there yet. This just shows when an appointment can start.

“Time increments” refers to the times students can choose from to start an appointment. Since mine is set to 30 minutes, students see times like 12pm, 12:30pm, 1pm, etc. If this were set to, say, 15 minutes, students would see 12:15pm, 12:30pm, 12:45pm, etc. This doesn’t affect how long the appointment may be. We’re not there yet. This just shows when an appointment can start.

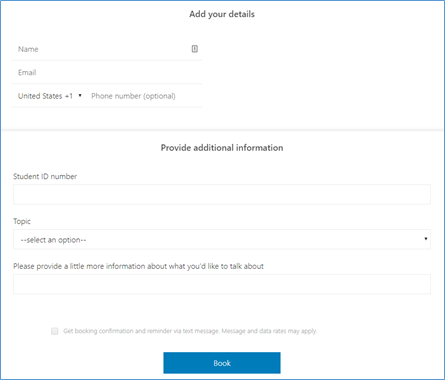

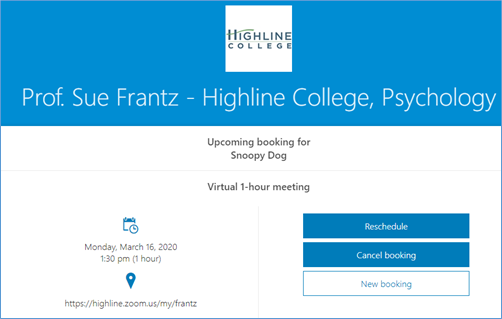

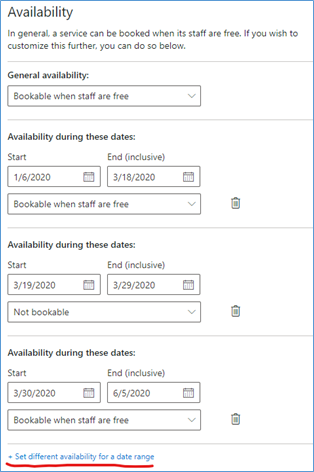

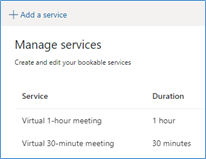

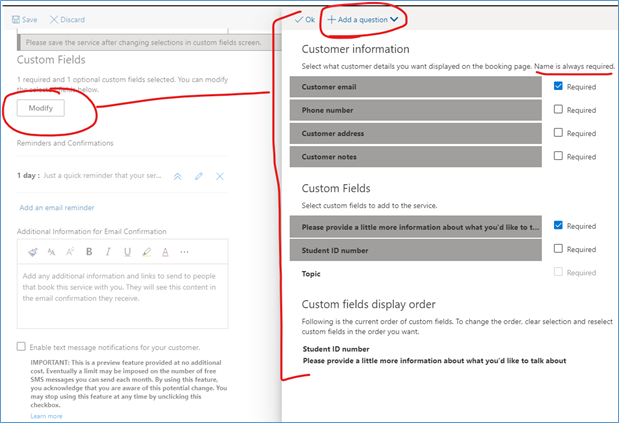

The “Services” page is where you create the different kinds of appointments students can make.

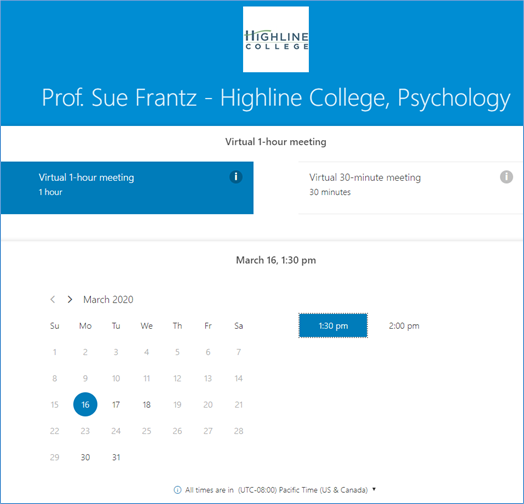

The “Services” page is where you create the different kinds of appointments students can make. Here, you can see that I have two “services”: virtual 1-hour meeting and virtual 30-minute.

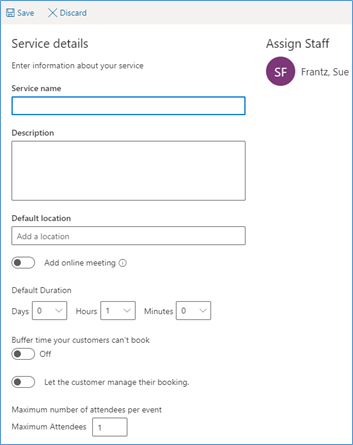

Here, you can see that I have two “services”: virtual 1-hour meeting and virtual 30-minute. The “service name” is what you want to call this type of appointment, such as “virtual 30-minute meeting.”

The “service name” is what you want to call this type of appointment, such as “virtual 30-minute meeting.”

Remember, as far as Office 365 Bookings is concerned, you’re a business. The “Business Information” page is all about you.

Remember, as far as Office 365 Bookings is concerned, you’re a business. The “Business Information” page is all about you.